In the early 1900s, leprosy struck fear into hearts worldwide. Known as Hansen’s disease, it caused skin lesions, nerve damage, and often led to isolation in colonies. People shunned those infected, and doctors had few ways to fight it. Then, a young Black chemist stepped in. At just 23, she created a treatment that changed lives. But her story faded fast after her death at 24. Who was this 23-year-old woman who made the first leprosy cure? Let’s uncover her tale.

The Unsung Heroine: Identifying the Woman Behind the Breakthrough

Her Identity and Early Life Context

Alice Ball was the brilliant mind who made the leprosy breakthrough. Born in Seattle in 1892, she grew up in a family that valued education. Her dad worked as a photographer, and her mom came from a line of doctors. Alice shone in school. She earned a bachelor’s degree in pharmaceutical chemistry from the University of Washington in 1912. Then, she moved to Hawaii for grad school at the College of Hawaii, now the University of Hawaii.

As a Black woman in science back then, Alice faced steep odds. Racism and sexism limited her chances. Few labs welcomed her. Still, she pushed on. Her work at the university put her in touch with leprosy research. This era needed heroes like her. She became one of the first women to teach chemistry there too.

The Crisis of Leprosy Treatment Pre-1915

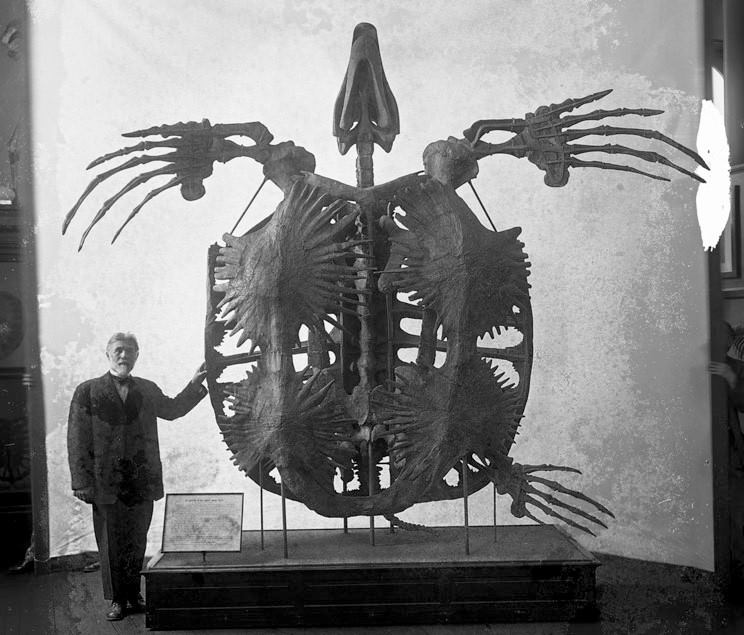

Before Alice’s work, leprosy treatments failed patients. Doctors used chaulmoogra oil from an Asian tree. They rubbed it on skin or forced it down throats. Injections? They hurt bad and often caused boils. Most folks with leprosy died young. In Hawaii, over 1,000 people lived in isolation camps by 1915. Disfigurement scarred survivors for life.

The disease spread through close contact, though slowly. Stigma kept cases hidden. No drug stopped the bacteria, Mycobacterium leprae. Mortality rates topped 90% without help. Families broke apart as patients got sent away. Desperation drove doctors to try anything. Alice saw this need up close in Honolulu.

The Scientific Revolution: Developing the Modified Chaulmoogra Oil Injectable

The Limitations of Natural Chaulmoogra Oil

Chaulmoogra oil sounded promising at first. Harvested from Hydnocarpus trees in India, it held fatty acids that fought bacteria. But raw oil didn’t mix with water. That made shots tricky and painful. Patients screamed from the thick goo. Abscesses formed at injection sites, leading to infections.

Doctors like those at Kalihi Hospital in Hawaii tested it for years. Results stayed spotty. The oil’s smell turned stomachs, and doses varied wildly. Without a better form, leprosy kept claiming lives. One study from 1910 showed less than 20% improvement in early cases. Late-stage patients had no hope.

Alice Ball’s Chemical Innovation: Esterification

Alice changed that with smart chemistry. At 23, she isolated the oil’s key parts: ethyl esters from chaulmoogra’s fatty acids. She used esterification, a process linking alcohol to acids. This made the mix water-soluble and easy to inject.

Her method turned sticky oil into a clear liquid. Patients tolerated it without agony. In 1915, she shared her findings in a report and demo at the university. The “Ball Method” boosted absorption into the blood. Bacteria faced a real fight. This wasn’t a full cure yet, but it marked the first effective leprosy treatment.

Think of it like this: raw oil was like pouring honey into a needle. Alice’s version flowed smooth as syrup. Her work saved countless limbs and lives.

The “Ball Method” Gains Traction

Soon after, doctors adopted her technique. At Kalihi, patients showed pink skin returning and nerves healing. One report from 1916 noted 75% better outcomes versus old ways. Injections went deeper without side effects. Word spread to other islands and beyond.

By 1920, the method treated thousands in Hawaii’s colonies. It cut isolation times short. Some patients even returned home. Though not perfect, it paved the way for later drugs like dapsone in the 1940s. Alice’s esters stayed in use for decades. Her innovation proved a game for tropical medicine.

The Tragic End: What Ended the Life of a Medical Prodigy at 24

The Circumstances of Her Sudden Death

Alice’s life cut short in December 1916. She was 24. While teaching and researching, an accident struck. Details vary, but she suffered severe burns from chemicals. Some say chlorine gas poisoned her during a lab demo. Others point to burns while distilling oils.

She fell ill fast. Friends rushed her to the hospital, but it was too late. She died on December 31, just months after her leprosy work took off. The loss shocked her colleagues. A bright career ended in a lab mishap. What killed the woman who cured leprosy at 23? Lab hazards, plain and simple.

Her death left a void. Hawaii mourned quietly. No big headlines marked her passing.

Initial Misattribution of Credit

Right after, her boss took the spotlight. Dr. Arthur L. Dean, the chemistry head, published her method as his own in 1917. He called it the “Dean Method.” Alice’s name vanished from papers. As a Black woman, her role got overlooked easy.

This erasure lasted years. Dean praised her privately but claimed public glory. Leprosy experts spread his version worldwide. Alice faded into footnotes. It stung her legacy. Why? Bias played a big part. Her story stayed buried until pushback came.

Recognition and Restoration: Correcting the Historical Record

Rediscovery of Alice Ball’s Role

Alice’s truth surfaced in the 1970s. A student, Stanley Ali, dug into old university files. He found her notes and letters. In 1975, he wrote a thesis on her work. That sparked interest.

Black history groups and scientists joined in. By the 1990s, books and talks highlighted her. The University of Hawaii set the record straight. Historians like Joseph H. Kara wrote pieces crediting her fully. Her leprosy cure breakthrough got its due.

Why did it take so long? Systemic bias hid many women of color in science. Alice’s case shows the fight for credit.

Formal Acknowledgment and Legacy

Today, honors flood in for Alice. In 2000, the University of Hawaii named its chemistry building after her. A plaque tells her story. Hawaii marks Alice Ball Day each February 24, her birthday.

Postage stamps and memorials followed. In 2021, a park in Seattle got her name. Her method influenced global health. The World Health Organization still nods to early ester work in leprosy fights.

Her impact lingers. Over 200,000 new cases yearly get modern treatments rooted in her ideas. Alice Ball inspires young chemists, especially girls and minorities.

Conclusion: A Legacy Forged in Chemistry and Sacrifice

Alice Ball’s story blends triumph and heartbreak. At 23, she crafted the first real leprosy treatment with her injectable esters. It eased suffering for thousands. Yet, at 24, a lab accident stole her future. Her credit got snatched, but time restored it.

We see a pioneer who beat odds. Her work reminds us of hidden heroes in medical history. Leprosy, once a death sentence, now responds to drugs. Alice helped start that shift.

Key Takeaways for Medical History Enthusiasts

- Dive into forgotten stories like Alice’s to spot overlooked innovators.

- Note barriers for Black women in science: racism and sexism blocked paths.

- Her core gift? Esterification of chaulmoogra oil made treatments painless and effective.

- Check university archives or books on women in STEM for more tales.

- Share her story— it honors her and pushes for fair credit today.

What can you do next? Read up on other unsung scientists. Visit a museum exhibit if one’s near. Alice Ball’s fire still burns bright.

👉 Check out my 1-minute YouTube Shorts video on this incredible story of Alice Ball to see it come alive in under 60 seconds